Masonic, Occult and Esoteric Online Library

Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art

By John Vinycomb

Other Chimerical Creatures and Heraldic Beasts- The Salamander

The salamander has been immemorially credited with certain fabulous powers. Less than a century ago the creature was seriously described as a "spotted lizard, which will endure the flames of fire." Divested of its supernatural powers it is simply a harmless little amphibian of the "newt" family, from six to eight inches in length, with black skin and yellow spots. The skin was long thought to be poisonous, though it is in reality perfectly harmless; but the moist surface is so extremely cold to the touch that, from this peculiar quality in the creature, the idea must have arisen, not only that it could withstand any heat to which it was exposed, but it would actually subdue and put out fire.

This was a widespread belief long before the time of Pliny, whose account of the creature is thus paraphrased by Swift:

"Further, we are by Pliny told

This serpent is extremely cold;

So cold that, put it in the fire,

’Twill make the very flames expire."

Marco Polo, the early Venetian traveller, who tells of many strange and wonderful things seen and heard of in his journeyings, was not a believer in the fabulous stories of the salamander, for he dismisses the subject with the curt remark, "Everybody knows that it could be no animal's nature to live in fire." An early heraldic writer of a somewhat later period, with greater credulity, stoutly maintains its reality, and in describing the creature states that he actually possessed some of the hair or down of the salamander. "This," he goes on to say, I have several times put in the fire and made it red-hot, and after taken out; which, being cold, yet remaineth perfect wool, or fine downy hair."

Marco Polo further on assures his readers that the true salamander is nothing but an incombustible substance found in the earth, "all the rest being fabulous nonsense." He tells of a mountain in Tartary, "there or thereabouts," in which a "vein" of salamander was found; and so we arrive at the fact that this salamander's wool was nothing but the "asbestos" of the ancients. It is easy to see why asbestos became known as "salamanders’ wool." The name resulted from the juxtaposition of ideas, and shows how deeply impressed was the belief in the salamander's mysterious powers. A late writer tells us that some of the lizard tribe are known to enjoy warmth, and alligators are said to revel in hot water. It needed only that an insignificant member of the genus should have been found among the dead embers of a fire to prove at once the invulnerability of the reptile and its ability to extinguish the flames.

The salamander of mediæval superstition was a creature in the shape of a man, which lived in fire (Greek, salambeander, chimney-man), meaning a man that lives in a chimney. It was described by the ancients as bred by fire and existing in flames, an element which must inevitably prove destructive of life. Pliny describes it as "a sort of lizard which seeks the hottest fire to breed in, but quenches it with the extreme frigidity of its body." He tells us he tried the experiment once, but the creature was soon reduced to powder. *

Gregory of Nazianzen says that the salamander not only lived in and delighted in flames, but extinguished fire. St. Epiphanius compares the virtues of the hyacinth and the salamander. The hyacinth, he states, is unaffected by fire, and will even extinguish it as the salamander does. "The salamander and the hyacinth were symbols of enduring faith, which triumphs over the ardour of the passions. Submitted to fire the hyacinth is discoloured and becomes white. "We may here perceive," says M. Portal, "a symbol of enduring and triumphant faith."

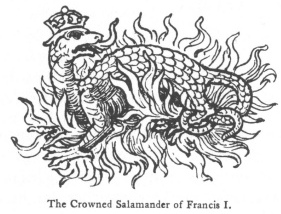

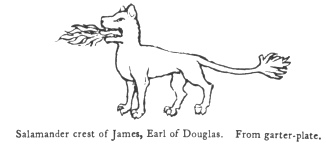

This imaginary creature is generally represented as a small wingless dragon or lizard, surrounded by and breathing forth flames. Sometimes it is represented somewhat like a dog breathing flames. A

golden salamander is so represented on the garter-plate of James, Earl of Douglas, K.G., the first Scottish noble elected into the Order of the Garter, and who died 1483 A.D. Tinctured vert; and in flames proper it is the crest of Douglas, Earl of Angus.

François I. of France adopted as his badge the salamander in the midst of flames, with the legend, "Nutrisco et extinguo" ("I nourish and extinguish"). The Italian motto from which this legend was borrowed was, "Nudrisco il buono e spengo it reo" ("I nourish the good and extinguish the bad;" "Fire purifies good metal, but consumes rubbish"). In his castle of Chambord, the galleries of the Palace of Fontainebleau, and the Hôtel St. Bourg Thoroulde at Rouen, this favourite device of the crowned salamander, with the motto, may be everywhere seen.

Azure, a salamander or, in flames proper, is the charge on the shield of the Italian family of Cennio.

The "lizards" which form the crest of the Ironmongers’ Company, were probably intended for salamanders on the old seal of the company in 1483, but are now blazoned as lizards.

The heraldic signification of the salamander was that of a brave and generous courage that the fire of affliction cannot destroy or consume.

In the animal symbolism of the ancients the salamander may be said to represent the element of Fire; the eagle, Air; the lion, Earth; the dolphin, Water.

Footnotes

211:* "Natural History," x. 67, xxix. 4.