Masonic, Occult and Esoteric Online Library

The Christian Creed

By C. W. Leadbeater

The Earlier Creeds

THERE are many students of Theosophy who have been, and indeed still are, earnest Christians; and though their faith has gradually broadened out into unorthodoxy, they have retained a strong affection for the forms and ceremonials of the religion into which they were born. It is a pleasure to them to hear the recitation of the ancient prayers and creeds, the time-honoured psalms and canticles, though they try to read into them a higher and wider meaning than the ordinary orthodox interpretation.

I have thought that it might be of interest to such students to have some slight account of the real meaning and origin of those very remarkable basic formulae of the Church which are called the Creeds, so that when they hear them or join in their recital the ideas brought [1] into their minds thereby may be the grander and nobler ones originally connected with them, rather than the misleading materialism of modern misapprehension.

I have spoken of the ideas originally connected with them; I ought perhaps rather to say the ideas connected with the ancient formula upon which all the most valuable portion of them is based. For I do not mean to say for a moment that any large number of the members, or even of the leaders, of the Church which now recites these Creeds have for many a century known their true meaning. I do not even claim that the ecclesiastical councils which edited and authorized them ever realized the full and glorious signification of the rolling phrases which they used; for much of the true meaning had already been lost, much of the materializing corruption had been introduced, long before those unfortunate assemblies were convoked.

But this at least does seem certain - that narrowed, degraded and materialized as the Christian faith has been, corrupt almost beyond recognition as its scriptures have become, an attempt has at least been made by some of the higher powers to guide those who have compiled for it these great symbols called the Creeds, so that, whatever they may themselves [2] have known, their language still clearly conveys the grand truths of the ancient wisdom to all who have ears to hear; and much that in these formulae seems false and incomprehensible when the endeavour is made to read them in accordance with modern misconceptions, becomes at once luminous and full of meaning when understood in that inner sense which exalts it from a fragment of unreliable biography into a declaration of eternal truth.

It is with the elucidation of this inner sense of the Creeds that I am concerned; and although in writing of this it will be necessary for me to make some reference to their real history, I need hardly say that I am not in any way attempting to approach the subject from the ordinary scholarly standpoint. Such information as I have to give about the Creeds is obtained neither from the comparison of ancient manuscripts nor from the study of the voluminous works of theological writers, but is simply the result of an investigation into the records of Nature made by a few students of occultism. Their notice was incidentally attracted to the question while following up quite another line of research, and it was then seen that the matter was of sufficient interest to repay further and more detailed examination.

It will perhaps be a new idea to some of my [3] readers that there is such a thing as a record of Nature - that there are methods by which it is possible to recover with absolute certainty the true story of the past. The fact that this can be done is well known to those who have studied the subject, and much ancient history of most vivid interest has already been examined in this way. To explain the process would be outside the scope of this treatise, and I would refer those who desire further information upon this matter to my little book on Clairvoyance.

The Christian Church at present uses three formulations of belief, called respectively the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Athanasian Creed. The first and second of these have many points in common, and may easily be examined together; the third is so much longer and so different in character, that it will be more convenient to devote a separate chapter to its consideration later. As at present found in the Prayer-book of the Church of England, these Creeds are as follows:

THE APOSTLES' CREED.

I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth; and in Jesus Christ his only Son our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and [4] buried; he descended into hell; the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of God the Father Almighty; from thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Ghost, the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting.

THE NICENE CREED.

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible; and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of his Father before all worlds, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made; who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man, and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; he suffered and was buried, and the third day he rose again according to the scriptures, and ascended into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of the Father; and he shall come again with glory to judge both the quick and the dead, whose kingdom shall have no end. [5]

And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and giver of life, who proceedeth from the Father and the Son, who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified, who spake by the prophets; and I believe one catholic and apostolic Church; I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins, and I look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.

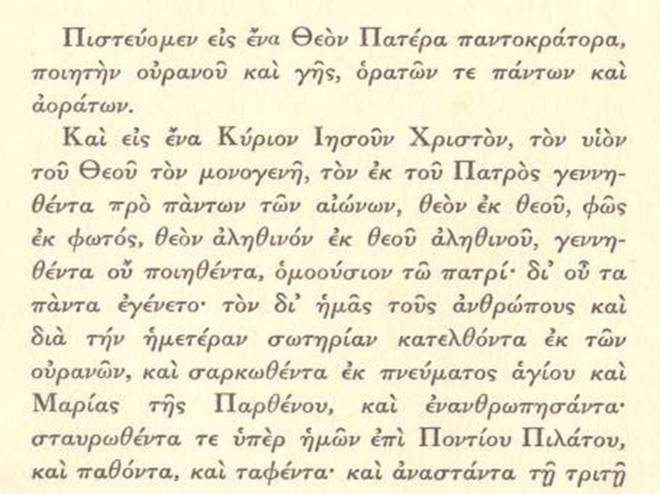

Since for the comprehension of the Nicene Creed so much depends upon accurate translation from the Greek original, I append here the received text for comparison.

Image 1

[6]

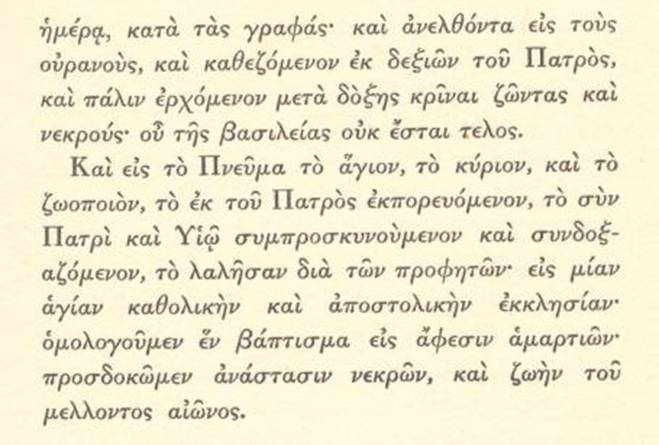

Image 2

THEIR DATE AND HISTORY.

Before describing the true origin of these Creeds, let me very briefly epitomize the current ideas of orthodox theologians as to their date and history. At one time the ecclesiastical theory was that the Nicene and the Athanasian formulae were merely amplifications of the Apostles’ Creed, but it is now universally recognized that the Nicene Creed is historically the oldest of the three. Let us take them one by one, and glance at what is commonly known of them.

Some sort of brief and simple Creed seems to have been in use from a very early period, not only as a symbol of faith, but as a pass-word in military style. But the wording of this formula [7] appears to have varied considerably in different countries, and it was not until centuries later that anything like uniformity was attained. An example of the earlier form is the Creed given by Irenaeus in his work Against Heresies: "I believe in One God almighty, of whom are all things … and in the Son of God, by whom are all things."

The earliest mention of a Creed bearing the name of the Apostles occurs in the fourth century in the writings of Rufinus, who states that it is so called because it consists of twelve articles, one of which was contributed by each of the twelve Apostles assembled in solemn conclave for the purpose. But Rufinus is not regarded as any great historical authority, and even in the Roman Catholic encyclopaedia of Wetzer and Welte his story is considered as a mere pious legend.

The Apostles' Creed is not found in anything like its present form till fully four centuries after the composition of the Nicene symbol, and the most authoritative writers on the subject suppose it to be a mere conglomerate slowly formed by the gradual collation of earlier and simpler expressions of belief. Occult investigation negatives this idea, as will be explained later, and, though quite admitting its composite character, assigns to part of it at any [8] rate a far higher origin than even that claimed by Rufinus.

Much more definite and satisfactory, from the ordinary point of view, is the history of the longer formula called the Nicene Creed, which appears in the mass of the Roman Church and the communion service of the Church of England. Practically all writers seem agreed that with the exception of two notable omissions it was drawn up at the Council of Nicaea in the year 325. As most readers will be aware, that council was summoned in order to settle the controversies then raging among ecclesiastical authorities as to the exact nature of the Christ. The Athanasian or materialistic party declared him to be of the same substance as the Father, while the followers of Arius preferred not to commit themselves to anything stronger than the statement that he was of like substance, nor were they willing to admit that he also was without beginning.

The point seems a small one to have caused so much excitement and ill-feeling; but it appears to be one of the characteristics of theological controversy that the smaller the difference of opinion the more acrimonious is the hatred between the disputants. Suggestions have been made that Constantine himself exercised a somewhat undue influence over the [9] deliberations of the council; however that may have been, its decision was in favour of the Athanasian party, and the Nicene Creed was accepted as the expression of the faith of the majority. As then drawn up, it ended (if we omit the awful anathema, which shows very clearly the real spirit of the council) with the words, "I believe in the Holy Ghost," and the clauses with which it now concludes were added at the Council of Constantinople in the year 381, with the exception of the words "and the Son," which were inserted by the Western Church at the Council of Toledo in the year 589. [10]