Masonic Stories

Shackleton, Freemasonry and the Quest for the South Pole

How did Freemasonry influence Sir Ernest Shackleton's legendary journey across Antarctica?

The story of Sir Ernest Shackleton and his quest to cross the south pole is one of Masonic endurance. There is, perhaps, no other trait or virtue more important in the moral teachings of Freemasonry, and it was these teachings that saved the ill-fated expedition from total ruin.

It was thus fitting that Shackleton, a Freemason and explorer, christened the boat purchased for his 1914 Antarctic Expedition - Endurance. With inspiration from the Shackleton family motto “Fortitudine vincimus" (By endurance we conquer), the three-masted wooden sailing vessel was built specifically for frozen seas; however, its first voyage into the ice fields of Antarctica would also be it last.

The early years of the twentieth century were known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, and the South Pole represented the planet’s final unknown frontier. In the published maps of the day, the Antarctic interior was a blank canvas upon which nations and ambitious men alike sought to make their mark. Having been a part of two previous expeditions to the continent, Brother Shackleton possessed experience and knowledge of polar climes.

In 1914, Shackleton answered his greatest call to adventure. He ambitiously set out to lead the first expedition across Antarctica starting from the coast of the Weddell Sea, traversing the South Pole and ending at the Ross Sea. Methodical in his planning, Shackleton began to assemble his crew. Shackleton placed the following advertisement in the London Times:

“Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.”

Shackleton was the rare sort of man who learned from his past mistakes and systematically sought to apply those lessons to his future endeavors. Knowing the psychological strain that the men would be forced to endure in the conditions of Antarctic, Shackleton required a crew that shared his idealistic vision and tenacious spirit - men like those in one of Shackleton’s favorite poems who longed to mark "the map's void spaces.” Reportedly, thousands of men sought a position on Ernest Shackleton's crew, and twenty-eight were chosen.

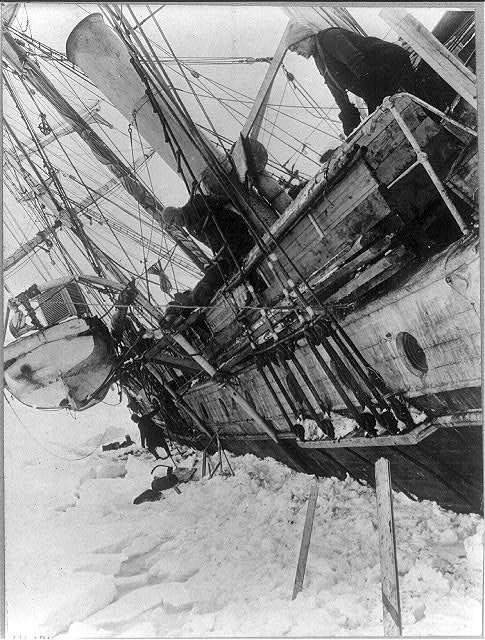

In August 1914, the ship set sail for Antarctica by way of South Georgia Island, a whaling settlement in the middle of the South Atlantic Sea. Heading south, the wooden ship immediately encountered problems navigating through unusually thick patches of ice that created a constantly shifting labyrinth of destruction. By January of 1915, the crew aboard the Endurance was able to see the Antarctic mainland, but bitterly cold temperatures and the polar winds had trapped the vessel in ice.

Locked in place, the crew had no choice but to wait until the warmer temperatures of spring could free the ship. Shackleton demonstrated great leadership skills, keeping all crew members occupied in strict routines to mitigate the collective fears and anxieties of the men on board. Months passed, and morale continued to sink as the ship remained held by the ice, despite the warmer temperatures of summer.

The sheer pressure of the ice was weakening the Endurance. Loud creaks and groans were interspersed with sharp explosions, reported by the crew to sound like gunshots and heavy fireworks, as the timbers of the ship were strained to breaking point. Crew member Tom McLeod exclaimed in fear, “Do you hear that? We’ll none of us get back to our homes again!”

The Endurance is legendary in the records of polar exploration, despite the fact that the expedition’s initial objectives were never achieved. The Endurance expedition was an epic failure as the ship was destroyed by ice before even reaching Antarctica. As the wood violently twisted and pinched on board the Endurance, Shackleton remained astonishingly calm, displaying remarkable self-control, optimism, and an almost casual indifference to the impending doom. Facing the collapse of his mission, Shackleton rejected defeat and set his sights on a new objective. He wrote at the time, “If the one goal has disappeared, we’ll have another one. And so, if I can’t cross the continent, I am going to bring all my men back alive.”

In this time of great crisis, how did the teachings of Freemasonry help the crew of the Endurance avoid an untimely demise? Having been initiated into Navy Lodge No. 2612 of the United Grand Lodge of England on July 9, 1901, Shackleton had learned the importance of ritual and fraternity in maintaining discipline, cohesion, and determination, in the face of overwhelming odds. In order to preserve solidarity among the crew, daily rituals were imposed by Shackleton on board the Endurance

After ordering the men off the sinking ship, Shackleton marched his crew out onto the ice with the barest of supplies to make camp. By April 1916, the ice began to break up and the men navigated in three row boats to the rocky, deserted refuge of Elephant Island. Knowing that inaction meant that all would perish there, Shackleton decided to attempt one of the most daring open-boat voyages in recorded history.

Because Shackleton displayed the utmost devotion and responsibility to his team, his men returned his commitment with fierce loyalty and uncompromising faith in his ability to bring them home safely. In the small rowboat, Shackleton and five of his crew managed to navigate 800 miles to South Georgia through hurricane force winds and raging seas utilizing only a sextant - a handheld tool that provides direction via celestial positioning. Imprecise readings would have meant the waves, winds, and current would have led the small craft into the open ocean and certain death.

Due to the unparalleled navigating skills of crew member Frank Worsley, the tiny boat made it to South Georgia, but they landed on the uninhabited side of the island. With almost no equipment, Shackleton and his men crossed 30 miles of uncharted mountains in 36 hours.

Reaching the whaling station, Shackleton then faced the problem of finding a vessel capable of undertaking a rescue. He sent an urgent telegram to London requesting assistance from the British Government but assistance was denied due to the country's struggles in World War I. Thankfully, when his government could not save the mission, his Brothers in Freemasonry answered his call of distress and assisted in the rescue of his men.

When the Chilean Freemason, Brother Luis Pardo, heard of the dire circumstances of the remaining men, he offered to pilot a steamer, the Yelcho, through dangerous waters to rescue the stranded crew of the Endurance. Pardo wrote to his father, "When you read this letter, either your son has died, or he has arrived at Punta Arenas with the castaways. I shall not return alone."

Traveling back to Elephant Island, Brothers Shackleton and Pardo rescued the remaining men on August 30, 1916. Upon their return to Chile, Bro. Pardo's Lodge, Harmony No. 1411 in Valparaiso, held an emergency meeting on Saturday the 13th of September to welcome Brother Shackleton and his crew and to recognize the efforts of the Brothers. It was thus stated that "Freemasons the world over rejoiced at the successful termination of Brother Shackleton's endeavors."

Freemasonry calls us to embark on a profound adventure in a realm unexplored and uncharted by most modern individuals. Through hard work and perseverance, the Craft provides the tools for the highest degree of moral, intellectual, and spiritual development for all Mankind. Moreover, it teaches us the skills of leadership and reminds us of our responsibilities to our fellow human beings, as exemplified by Brothers Shackleton and Pardo.